M&A is a complicated process requiring unique skills and difficult decision-making. According to the 2017 Private Capital Markets Report, (produced by Pepperdine’s Graziadio School of Business in January 2017 and covered the deal making market over the previous 12 months) 35% of all 2016 sell-side M&A transactions did not close. The number one reason, explaining 30% of all failed transactions, was a valuation gap between the seller and the buyer. 64% of the time, that gap was between 11% and 30%.1 Ultimately, an acquirer makes a “go” or ”no go” decision on closing the transaction. Hurdle rates, the cost of capital, and valuation are key factors in reaching that decision. Let’s take a look at each of these factors in more detail.

Hurdle Rate: Typically acquirers establish a hurdle rate for an acquisition – or a minimum rate that an acquirer expects to earn when investing in an acquisition. A hurdle rate is typically greater than the cost of capital for the target’s business. The hurdle rate delta is the difference between the hurdle rate and the target’s cost of capital. Management has to conclude that there is an attractive hurdle rate delta in order to create value from the acquisition.

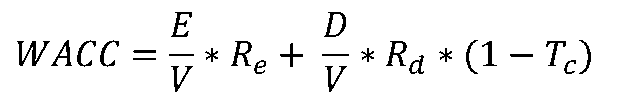

Cost of Capital: How does an acquirer calculate cost of capital (aka: discount rate) for an acquisition? The most often used measurement is the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (“WACC”). The WACC is applied to future cash flow streams of the target company. It helps the acquirer adjust the risk of the target’s future cash flow streams back to the present, and significantly influences a Discounted Cash Flow (“DCF”) method of valuation. Establishing this WACC benchmark for evaluating a prospective acquisition is an important step for acquirers. The formula to calculate WACC is

Where:

E = market value of the firm’s equity;

D = market value of the firm’s debt;

V = E + D = total market value of the firm’s financing (equity and debt);

Re = cost of equity;

Rd = cost of debt;

Tc = corporate tax rate.

and

E/V = percentage of financing that is equity;

D/V = percentage of financing that is debt.

1 Survey of 88 investment bankers.

Again, the hurdle rate should be greater than the cost of capital, or the WACC, in order for an acquirer to proceed in closing the transaction.

Valuation: First, the seller, should have prepared 3, 5 or 7-year detailed projections. Companies whose business and markets are evolving rapidly might consider a 3-year outlook. A company that has generated a consistent EBITDA in recent years, with confidence of hitting that number going forward should carry projections out 5 years. Finally, for companies with highly predicable revenue growth, and with consistent margins might consider a 7-year forecast.

Next, the seller needs to determine their company’s future Free Cash Flows. This is done by calculating an Earnings before Interest and after Taxes minus Capital Expenditures plus Depreciation and Amortization plus/minus changes in Net Working Capital.

Then one needs to apply the WACC to the target’s future Free Cash Flows to discount those cash flows back to the present. This establishes a value for the concrete period, or period of time covered in the projections. Also, one will still need to calculate a terminal value for the target. Establishing the WACC is an important step to reach a conclusion for the DCF valuation.

Taking all of these points into account, it is not too difficult to envision why valuation is the number one reason for failed M&A negotiations. It is complicated. Many sellers underestimate the significance of a professional valuation on their business. That can result in selling one’s business for less than market value. An example of this is how wide a range of multiples were paid to sellers in the home healthcare space. In a sample of 12 closed transactions2 in which the acquirers were all private equity groups, there was a huge range of multiples paid off of sales, from 3.5x to 7.5x EV/Sales, in deals where the purchase price was between $10MM to $25MM. In turn, in deals where the purchase price was $25MM to $50MM, the EV/Sales multiples tightened to between 5.5x to 7.5x, and for deals where the purchase price was between $50MM to $250MM the EV/Sales multiples tightened to 7.6x to 8.3x. While no deal or seller looks exactly alike, at the $10MM to $25MM deal level, valuation guidance appears to have been lacking for these sellers, which resulted in a wider range of multiples paid.

Again, M&A is a difficult, complicated process. Hurdle rates, cost of capital and valuation each are used by sophisticated acquirers to help make tough decisions when in the middle of an acquisition transaction. Sellers should master these tools too, or work with an investment banker, in order to better prepare during times of negotiating with the buyer.

2 Data from GF Data Resources.